Every fall, freshmen who pull up at their residence halls embark on an important journey: living on their own for the first time while navigating the uncharted waters of higher learning. But these young students are not completely alone. Many freshmen — and even many of their more experienced upperclassmates — come to campus accompanied by souvenirs and keepsakes they wouldn’t dream of leaving behind. From stuffed bears to security blankets, these mementos connect them to the comforts of home while they explore new frontiers.

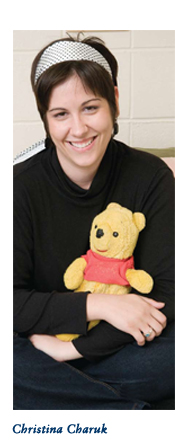

Christina Charuk’s grandmother gave her a Winnie-the-Pooh stuffed bear for her third birthday. It came with her the first day she arrived at FDU from Binghamton in upstate New York and remains a fixture in her Linden Court Residence Hall room on the Metropolitan Campus. Pooh-bear even went with Charuk to a semester at FDU’s Wroxton College in England. Today, his fur is flattened and his tummy is concave; one arm came off years ago and was sewn back on by Charuk’s grandfather — backward.

Indeed, the teddy bear may be a universal comfort object. Danushi Fernando, a graduate student in corporate and organizational communication at the College at Florham, is from Mount Lavinia, near Colombo in Sri Lanka. When she was born, her father gave her a fuzzy teddy bear. But when Fernando left home for the first time to attend FDU as a freshman in 2004, she didn’t have room for it in her luggage. Three days later in a panic, she was on the phone to Sri Lanka.

“My dad had to FedEx it to the United States,” she says of the stuffed bear, now in tatters. “I have so many memories connected with it. It reminds me of my family and all sorts of childhood stuff.” She has also decorated her Park Avenue Residence Hall room with posters of Sri Lanka and family pictures.

What psychologists call “transitional objects” can help a student feel more at ease away from home, says David Mednick, co-director of Student Counseling and Psychological Services (S-CAPS) on the Metropolitan Campus.

“Students need to feel comfortable, period,” he says. “They need to feel well — emotionally, physically and mentally. If they’re feeling too homesick, they’re not going to perform well academically.”

Some students literally bring security blankets from home, Mednick says: usually well-worn regular blankets and linens, but sometimes their actual baby blankets. “Or they’ll bring photographs or objects they got as souvenirs on family vacations or objects close friends gave to them — because they’re not only missing their families, they’re missing their friends,” Mednick says.

Pooh is hardly the only reminder of home for Charuk, a graduate student in English literature. “The biggest thing I have is the art my mom and I do together,” she says. (Charuk has spent a lot of time with her mother: She was home-schooled from kindergarten through high school.) Two watercolor and ink abstracts with nature themes, one by her mother and one of her own, decorate her room.

From Distant Lands

Almost 9 percent of FDU’s attendees are international students, from all corners of the globe, and their homesickness can be especially daunting. Mednick runs an annual orientation workshop for new international students; afterward, many of them tell him how difficult it is to be far from home in a place where the cultural norms, food and even the time zone are so different.

But international students usually find ways to adjust while retaining their culture and traditions, he says. Gerardo Nunez, a junior from Quito, Ecuador, who lives in the Lindens, treasures his Otavalo souvenirs. The Otavaleños, indigenous people who live in the highlands near Quito, are world-famous for their weaving, leatherwork, textiles and simple wooden toys. His favorite keepsake is a carving of a fisherman complete with movable fishing pole and string attached to tiny wooden fish. “It’s interactive — you can play with it,” he says.

Nunez also has figurines of Otavaleño women carrying baskets, symbolizing the region’s agricultural harvest. The handicrafts “remind me of home, family and friends,” he says.

When Nunez is asked if he still misses Quito and his family — his parents and two younger siblings — back home, he readily agrees. “This is the first time I’ve been away for such a long time. The first semester I was here, I missed my family, my house, my pillow, my dog, the weather.”

Even well-traveled students who are as comfortable in New Jersey as they are in Europe or Southeast Asia sometimes need a reminder of their cultural and family roots. May Taw is a senior biochemistry major and a resident assistant at her Linden residence hall. Her parents live in Indonesia now — her father worked for the United Nations, and she has lived in Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam — but she was born in Burma (now Myanmar). Her comfort object is a carved, black lacquer jewelry box from Burma given to her by an uncle who had it inscribed “So you’ll never forget home,” in Burmese.

“I got it when I was around 11 years old,” she says. “It’s the kind of thing that they make in small villages, and it has a picture of women working in the village.” Because she left Burma as an infant, the box is more important for its family connection than as a memento, she says.

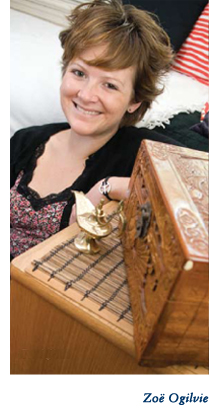

Similarly, Zoë Ogilvie treasures a family heirloom, a hand-carved rosewood jewelry box that she associates with the Brisbane, Australia, farm where she lived as a child. The box was passed down from Ogilvie’s grandmother to her mother and then to her. Her parents like to travel; the family left Australia when Ogilvie was 5 and moved to Indonesia, back to Australia and then to the Middle East. Six years ago, they moved to Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, the source of other treasures in Ogilvie’s room at FDU: an Arabic tea set, a small prayer rug and a brass lamp that reminds her of Aladdin’s.

Ogilvie, a junior who is active in student government, the campus newspaper and Business Leaders of Tomorrow, says the objects remind her of family and travel, but not necessarily of home. “I’ve moved around so much that home for me is a relative term,” she explains. “Home is where the people I’m closest to are. It may sound funny, but I think FDU is my home now.”

Athos Vardouniotis, a junior from Athens, Greece, has close relatives who live in New Jersey and New York, which helps keep homesickness at bay. He also has a battered blue notebook full of reminiscences and jokes scrawled in Greek and broken English by his high school friends.

“Friends of mine wrote ‘goodbye’ stuff in it, caricatures of themselves and our professors. It reminds me a lot of life back there,” Vardouniotis says. “If there were fun things said in classes, we wrote them down. It’s something to remember high school by — they don’t really have yearbooks there.”

He also carries family photos with him and brought some Greek books to FDU so he wouldn’t forget how to read his native language. “But I avoided bringing too much stuff from home, because then it would be a constant reminder to me,” he says.

Closer to the Comfort Zone

Students whose families live only hours away may have less exotic talismans, but they’re important just the same.

Meghan Droge, from North Merrick on Long Island, N.Y., is a member of the Division III Devils women’s volleyball team at the College at Florham. In her Rutherford Hall room, she displays pictures of close friends and family as well as inspirational quotations from the likes of Winston Churchill (“Success is never final. Failure is never fatal. It is courage that counts.”) and former UCLA basketball coach John Wooden (“Remember this your lifetime through — tomorrow there will be more to do. And failure waits for all who stay with some success made yesterday …”).

After arriving at FDU in 2006, she quickly made friends with her teammates and then others. “I’m from a close-knit family from a small town, where there’s lots of personal connections. But FDU is a small community itself, and you develop very similar kinds of feelings,” Droge says.

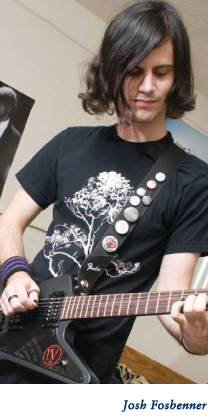

For Josh Fosbenner, a freshman in creative writing at the College at Florham, it’s his guitar, a black Epiphone Goth 1958 Explorer, that helps ease the pain of separation from family and friends back home in Quakertown, Pa.

“Music is really important to me in my life,” he says. “Listening to it is a major thing, going to concerts as well as playing, just myself or with my band.” Made up of Fosbenner and two friends from high school, the band is called Toils of Sleep; Fosbenner describes their style as “hard-core punk.” They write their own music, and when asked if he does vocals, he answers, “Technically, we don’t really sing.” They formed last February and have played two shows, but Fosbenner hopes there will be more gigs in the future.

The Explorer is only one of four guitars Fosbenner owns — two acoustic, two electric — but it’s his favorite because he bought it with his own money, mostly from his earnings last summer at Dorney Park, the amusement park not far from his home in Bucks County.

Hungry for Home

After family and friends, familiar food may be the aspect of home most missed by college students. Unlike his father, Fosbenner is not a fan of scrapple, the iconic pork and cornmeal dish of his home state, but he misses a brand of ice tea that he has not been able to find in New Jersey. Taw longs for spicy Southeast Asian food, especially mie goreng, a noodle dish that is sold dried in packets like ramen. Her mother sends her shipments twice a year, along with fiery sambal powder and sauce, but the mie goreng is usually gone within a month, she says. Ogilvie favors Moroccan peppermint tea or Arabic coffee “in tiny cups, very strong — you can’t get that at Starbucks.” Nunez misses his mother’s ceviche, while Fernando has yet to find dal (lentil stew) as good as her mom’s. Vardouniotis has fond memories of authentic pastitsio, the Greek baked pasta.

Charuk, whose family background is Ukrainian, doesn’t have to pine for homemade goodies. “My grandmother is always sending me random food,” she says, laughing. “She sends cookies in a shoebox, and they don’t break — it’s ridiculous. She’ll freeze a dinner, triple-wrap it and overnight it.” But the ultimate treat may be her grandmother’s pierogi, both the traditional potato-and-sour-cream version as well as the dessert variety, filled with blueberries or cherries and with butter and sugar on top. “They’re delicious!”

Mednick notes that as students make connections with other students from home, they learn where to find the food they miss, either near campus or in Manhattan, a virtual United Nations of international dining. At the same time, all students need to experience personal growth beyond the limits of home and family, he says.

“Part of college is learning and opening up to new experiences, so students should explore new things, and that includes people, food and new ways of doing things,” Mednick says. “Often I have the pleasure of watching a student — who had come in saying she wants to go home and drop out — go through the process I just described. Now she’s got a large network of friends here, and she’s doing well in school and emotionally and socially.”

Still, today’s students — even those thousands of miles from home — have a big advantage over those of yesteryear: modern communication technology. “Luckily, in this day and age, we see less homesickness because we have so much connectivity,” Mednick says. E-mail, Internet phone service, texting and video chats have gone a long way to ease the fears and loneliness that all students feel at some time.

But what if homesickness strikes despite all the new friends and meaningful experiences? When Vonage and Facebook aren’t enough, there’s always Pooh-bear.

FDU Magazine Home | Table of Contents | FDU Home | MyFDU.net | Blog About It

©Copyright 2009 Fairleigh Dickinson University. All rights reserved.

For a print copy of FDU Magazine, featuring this and other stories, contact Rebecca Maxon, editor,

201-692-7024 or maxon@fdu.edu.