A Candidate for Heroism

Born and raised in Brooklyn, N.Y., George Tabeek, Jr., grew up as a third-generation American whose grandparents had immigrated to America from the Middle East around the turn of the century. His father, George, was a hard-working marine engineer in the Merchant Marine who spent months at a time on voyages around the world, until he finally landed a job working for the City of New York. His mother, Marie, meanwhile, had been tasked with bringing up the couple’s three children (George, Robert and Karen Ann).

Like thousands of other American kids growing up in Brooklyn during the 1950s and early 1960s, Tabeek had played endless games of stickball and touch football on the streets of his middle-class neighborhood. He’d rooted furiously for his beloved Brooklyn Dodgers … and then had endured pangs of grief after the team moved unexpectedly to Los Angeles in 1958. As a devout Catholic altar boy, Tabeek had been educated by the dedicated and demanding nuns who staffed the elementary school at his local parish church, St. Ephrem’s, on Fort Hamilton Parkway.

Tabeek was a bright, eager student, especially good in mathematics and science. By the time he graduated from his public high school in Brooklyn, he knew that he wanted to become an engineer like his father. After a brief stint at the New York City Community College (now New York City College of Technology of the City University of New York), Tabeek landed on FDU’s Metropolitan Campus in Teaneck, N.J., in 1970. “I learned a lot about the practical side of engineering at Fairleigh Dickinson,” he recalls, “and I think that was because so many of our professors had hands-on experience in their fields.

“They were very knowledgeable about the real world, because most of them were out there working as engineers or building designers and managers. They taught us a great deal about the practicality of things — and that really helped me later, after I got my degree in mechanical engineering technology [in 1973] and landed my first job as a field engineer in the Electrical and Mechanical Power Generation Division of General Electric.”

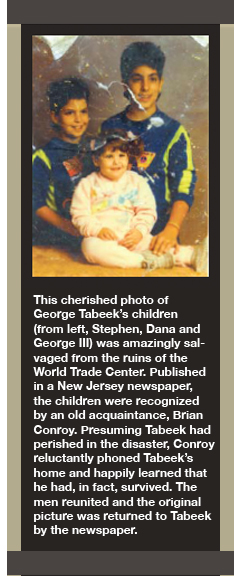

During his 11 years at the multinational corporation, Tabeek traveled the world while developing a variety of specialized, high-tech skills as an engineer who supervised construction, maintenance and safety in both fossil and nuclear-fuel generation, as well as other related projects. But with two young children at home (George III and Steven), he and his wife, Karen Ann, found his ceaseless globe-trotting for GE to be an increasingly heavy burden — and both of them were greatly relieved when he secured a position as a structural project manager for the fast-growing Port Authority of New York and New Jersey in the early 1980s.

What followed was a highly successful career in which Tabeek worked at a variety of transportation management tasks. But then, after the deadly car-bombing of the WTC in 1993 (six people were killed and more than 1,000 were injured), the Port Authority began designing a massive new security system for the huge complex at the foot of Manhattan. Because Tabeek had studied security issues extensively at GE, he was a natural candidate to fill the post of security manager and took over as the WTC’s top safety executive in 1999.

Ironically, George Tabeek had been deeply traumatized by the 1993 bombing — during which a group of Islamic terrorists had attempted to knock one tower into the next, hoping to bring both down and to kill as many as 50,000 people. He recalls telling himself, “I will never let them hurt my people like that again.”

“By 2001, we had put thousands and thousands of hours into safety construction and safety procedures,” he says. “We had bullet-proof window glass in most areas and security cameras everywhere. We had put together a series of evacuation plans and plans for how we would handle emergency response by fire and police. Really, the World Trade Center was safer on 9/11 than 99 percent of the buildings in America.”

He pauses for a moment, then shakes his head in mournful frustration. “But it still happened. We had planned for the possibility of a small airplane — a corporate jet, maybe — crashing into one of the buildings by accident. But these were jumbo jetliners loaded with fuel, and the terrorists were crashing them on purpose into the towers.

“How do you plan for that?”

Bravery in the Line of Duty

After surviving the initial jetliner impact at the North Tower (“I ran for cover between Buildings 2 and 4”), Tabeek got on his hand-held radio and began to alert his security staffers: “This is S-2 [his code name]. We have an emergency in Building No. 1. I’m going to assess the damages, and you should stand by for further instructions.” Within a few minutes, he had managed to fight his way into the North Tower, the site of the WTC Fire Command Station on the Concourse level. After checking in with the fire safety directors there and coordinating their first response, he hurried outside to the Promenade level in order to visually assess the damage as best he could. What he saw was terrifying to behold; the entire building was swaying badly, and people were falling from windows high above.

But his nightmare struggle to help both the WTC tenants and his own security staff escape from the building was only beginning. A short time later, he was answering a call that described how three of his security staff were trapped by debris in the North Tower’s 22nd-floor Security Control Center.

Without thinking about his safety — and accompanied by a team of firemen led by 44-year-old New York City firefighter Lt. Andy Desperito — Tabeek began the arduous climb up to the 22nd floor. The team carried more than 100 pounds of rescue gear, and while they were resting on the seventh floor, felt the whole building rock as the second hijacked jetliner smashed head-on into the South Tower, although they didn’t know it yet.

“I fell to the floor with the phone still to my ear I heard someone on the phone scream, ‘We are going to die!’” But Tabeek didn’t. Somehow, he and Desperito clawed their way to Floor 22, where the firemen tunneled through the wreckage to save several injured and badly frightened Port Authority staffers. After sending them down the stairs toward safety — without knowing that the South Tower had already collapsed (at 10:05 a.m.) — the two waited, ready to carry out any further instructions from the Command Center. The North Tower was creaking and swaying; but when Tabeek warned Desperito that they should run for it, the firefighter refused. Displaying amazing courage, he told Tabeek: “Without an order from Command to evacuate, we will stay on duty here — and if necessary, we will die with our brothers.”

A few moments later, the phone rang: Port Authority Police and Fire Command had just ordered that the North Tower be completely evacuated. They complied, and started the long trek down to the street — helping several injured people along the way and freeing others from piles of wreckage.

FDU Magazine Home | Table of Contents | FDU Home | MyFDU.net | Blog About It

©Copyright 2008 Fairleigh Dickinson University. All rights reserved.

For a print copy of FDU Magazine, featuring this and other stories, contact Rebecca Maxon, editor,

201-692-7024 or maxon@fdu.edu.