“In times of dif-

ficulty we turned

to each other. In

times of need we

learned to depend

on each other.

We laughed toge-

ther. We cried

together. We

lived together.

And some of us

will remain

friends forever.”

Nursing the Wounded

Glennena Haynes-Smith joined the United States Army Nurse Corps in 1988 after a recruiter told her she would be able to “see the world.” Fifteen years later, as a member of the Army Reserve, she knew it was just a matter of time before she would see the Middle East. “When the Iraq War began, I knew my unit would be affected sooner or later,” she recalls. “Once there is combat, there will be injuries; and once there are injuries, there will be a need for medical units.”

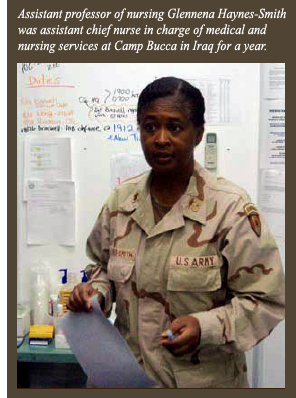

The assistant professor in FDU’s Henry P. Becton School of Nursing and Allied Health was involuntarily mobilized and deployed to Iraq in June 2005. “I was assigned to a base called Camp Bucca, named for a New York City Fire Marshal who lost his life as a result of the attack on the World Trade Center on September 11,” explains Haynes-Smith. The base is located in the middle of the desert in southern Iraq and houses more than 10,000 Iraqi detainees who are awaiting trial for a variety of crimes. Haynes-Smith’s unit provided medical care not only to the detainees, but also to the nearly 2,000 coalition forces and U.S. civilians stationed on the base and in the area.

Haynes-Smith was the assistant chief nurse responsible for medical and nursing services. “Many of the supporting departments reported to me, such as nutrition, rehabilitation, radiology and the operating room,” she explains. “Because of a shortage of nurses, I also worked in the intensive care unit, and when there were mass casualties, I rolled up my sleeves and worked in the emergency room.”

“Many of the supporting departments reported to me … and when there were mass casualties, I rolled up my sleeves and worked in the emergency room.”

For many medical professionals on base, treating Iraqi detainees was a complicated emotional struggle. “I went through a gamut of emotions from frustration to hostility,” explains Haynes-Smith. “We all had to remember that our mission was to provide medical and nursing care — not to judge. We were guided by medical ethics, made medically appropriate decisions and provided humane treatment.”

For the most part, she says, the Iraqis were grateful for the care provided. “We did have some cultural difficulties when some of the male Iraqis had to receive care from female soldiers, but these issues were usually resolved,” says Haynes-Smith.

The physical and emotional difficulty of day-to-day life created a special bond between unit members on the base. “The relationships we formed will most likely last a long time,” says Haynes-Smith. “In times of difficulty we turned to each other. In times of need we learned to depend on each other. We laughed together. We cried together. We lived together. And some of us will remain friends forever.”

“Seeing so much

trauma — and in

some cases, death —

has made me more

appreciative of life.

I do not ‘sweat the

small stuff’

anymore, and

everything now is

‘small stuff.’”The experience has given Haynes-Smith new perspective on life. “Seeing so much trauma — and in some cases, death — has made me more appreciative of life. I do not ‘sweat the small stuff’ anymore, and everything now is ‘small stuff,’” she says. She was moved by the hardships of Iraqi life, especially for children. “It’s important for others to know that the people who are suffering the most are Iraqi children. They are subjected to poverty, hunger and lack of health care. There is so much sadness in their eyes,” she says.

It was very upsetting for Haynes-Smith to be away from her own family for such a long period of time, and many aspects of her life were disrupted. “Now that I’m back, I feel as though I have missed so much. I feel I have lost a period in my life that I cannot recapture,” she says.

The time away also affected her professional life. “As a faculty member on a tenure track, there are certain activities that are expected of me, such as pursuing scholarly activities,” she says. “Because of my absence, fulfillment of these requirements has become a challenge.”

Haynes-Smith returned to the United States in June 2006. “Trying to readjust to life was — and still is — difficult. I do not think anyone could return from such profound experiences without suffering from some degree of post-traumatic stress disorder,” she says. She has resumed daily life and returned to teaching at FDU, but says, “I think that complete re-adjustment will take time.”

— M.E.B.

More Pictures From Glennena Haynes-Smith

Surgeon Proud | Soldier’s Story | Volunteer Meets Refugees

Scales of Justice | Article Home

FDU Magazine Home | Table of Contents | FDU Home | Alumni Home | Comments

©Copyright 2007 Fairleigh Dickinson University. All rights reserved.

For a print copy of FDU Magazine, featuring this and other stories, contact Rebecca Maxon, editor, 201-692-7024 or maxon@fdu.edu.