Two centuries ago, American explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark completed a famous and inspiring trek that would change the course of American history. The expedition, called the Corps of Discovery, set out from St. Louis, Mo., on May 14, 1804, to explore the vast wilderness of the Louisiana Territory, which had just been acquired from France, and beyond to the western coast of the new nation.

Penetrating a territory known only through rumor and conjecture, Lewis and Clark’s team embarked on a perilous journey that would last 28 months, bring them up the Missouri River and lead over the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean and back. The 1803 Louisiana Purchase had doubled the physical size of the young country, but it was the explorers’ return on September 23, 1806, that truly opened up the territory for American expansion.

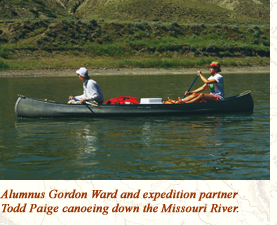

In the 200 years since that historic trip, many have crossed the continent, but perhaps no one has retraced the footsteps as faithfully as FDU graduate Gordon Ward, BA’81 (M). In the 200 years since that historic trip, many have crossed the continent, but perhaps no one has retraced the footsteps as faithfully as FDU graduate Gordon Ward, BA’81 (M). Ward completed a 1,800-mile retracing of Lewis and Clark’s trail from Bismarck, N.D., to the mouth of the Columbia River at the Pacific Ocean, the boundary dividing Washington and Oregon. He and his expedition partner, Todd Paige, cycled, backpacked and canoed a winding ribbon of modern highways, gravel roads, wild and scenic rivers and mountain trails.

While their journey took place in the mid-1990s, their adventures have now been chronicled in the recent publication of Ward’s Life on the Shoulder: Rediscovery and Inspiration along the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Ward, whose father, Warren, was a professor of biological sciences at Fairleigh Dickinson's campus in Madison from 1959 to 1981, describes himself as an experiential education specialist who “values the power of direct experience.” Combine that trait with a great passion for the outdoors, a worthwhile cause and a personal connection, and the allure of the trip was too great to resist.

Ward explains, “Our journey was dubbed Quest West, and its original purpose was to raise funds for a scholarship at an independent school in New Jersey where Todd and I taught, something we succeeded in doing. Inspired by our friend Louis Starr, we selected the Lewis and Clark Trail because of his personal association with William Clark’s diaries. Starr inherited the documents after they were discovered in December of 1952 in a rolltop desk that belonged to his grandfather.” The historical papers today can be found at the Beineke Rare Books and Manuscript Library at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

| On one level, he was traveling back through time, experiencing the places known and recorded in the pages of history ... But at the same time, he was also journeying through the modern-day American West ... |

|---|

Lewis and Clark preserved their thoughts and exploration experiences in journals that are still read and enjoyed today as one of this country’s first written descriptions of the land west of the Mississippi River. Following this same formula, Ward wrote a detailed travel journal. In fact, Life on the Shoulder is presented in its original journal format, as a modern record of a journey completed in the very footsteps of the rugged Corps of Discovery.

“This approach allowed me to best capture the flavor of the trip,” says Ward, “and I feel it also serves as one of the few common bonds between the two expeditions. To further highlight the similarities and the differences, all of my daily entries include passages from the Lewis and Clark journals that remark upon similar events and situations.”

Ward says that his journey took place on different levels. On one level, he was traveling back through time, experiencing the places known and recorded in the pages of history and the journals of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. But at the same time, he was also journeying through the modern-day American West, “an area of diverse environments, staggering beauty and powerful, natural forces.”

While he had worked hard and was prepared to connect with history, Ward says he gained so much more from the experience. “The landscape through which we traveled proved to be one of emotional hills and valleys, mountains of elation, pits of exhaustion, prairies of boredom, storms of fear, anger and frustration and stunning sun flashes of inspiration. It was a discovery of self and my connection with everything outside of my being.”

He adds that the trip was filled with many spectacular highlights, all of which were balanced with intense and unforeseen challenges. “There was a violent storm that halted our progress in central Montana,” Ward recalls. “Huddled in a tent on open rangeland, the only other person we saw for two days was a man who had the job of grading the weeds off the middle of the dirt road.

“We learned from him that one of the roads we intended to take was impassable, and we had to alter our route. Making our way through vicious winds and away from the river, we found ourselves in an area with little water, and we were quickly becoming dehydrated.

“To make matters worse, our cell phones had no service, and our new water purifier broke when we attempted to filter water from a drainage ditch, the only water source we had encountered in two days. No one knew where we were, and we were in a serious situation. To our amazement, our support vehicle driver, who was concerned about how we weathered the storm, went looking for us and found us only by coming upon the same road grader, the only other person in that extent of country!”

| “While Lewis and Clark have been credited with exploring the western wilderness, I believe the exploration of the greatest wilderness lies just beneath the skin in the hearts and minds of us all.” |

|---|

From the lush, northwest rain forests of the Cascades and the Oregon coast to the deserts of eastern Washington, Ward says he was in awe of the diversity of the West. It also became crystal clear how powerful the forces of nature really are. He remarks, “One can plan for a trip, but there are always unforeseen events that will punctuate and upset expectations and itineraries.

“The White Rocks section of the Missouri River, with all its fantastic rock formations, was something we anticipated because we were going to be on the river in the same manner that Lewis and Clark had been. Little did I know that it was the place where I was to become very ill, and Todd would have to paddle me out and get me to a hospital. It turned out I had Lyme Disease, and, I was told, the first documented case in Montana.

“My favorite memory from the six-week trip is sitting in a meadow along the Lolo Trail in the Bitterroot Mountains of northern Idaho. Staring off at ridge after ridge of mountains, graying out into the distance made me extremely aware of how small we are as individuals, and I remember how serene and peaceful it was. We had just finished our second day of backpacking. The first day had taken us up a trail with a 3,200-foot total elevation gain, which was impossible to follow due to its lack of use. We ended up running out of water. I had stopped sweating in the 96-degree heat, and Todd’s legs were shaking uncontrollably. After bushwhacking up the ridge and locating the Lolo Trail, a remote route that is accessible in places by four-wheel-drive vehicles, we collapsed on the side of the trail to rest. At that very moment we heard an engine. Remarkably, a car carrying a man and a woman stopped, and they gave us water, told us where to find a spring and simply drove away.”

As the title of his book indicates, Ward says that a great deal of his time was spent literally riding “on the shoulder” of many roads and passing many sights “while we, in turn, were passed by many other travelers. It provided many opportunities for observation and reflection. The analogy to life became quickly apparent. By living a ‘life on the shoulder,’ one allows oneself to step back, become more aware and permit life’s events to unfold naturally, at their own pace. In doing so, one is given the opportunity to realize, with a clearer understanding, the connections and interrelationships that exist between and among all things.”

Since the trip, Ward has been busy writing and lecturing about his experiences. His next book, A Bit of Earth: Preserving Childhood, History, and a Sense of Place, is scheduled to be published in December. This collection of stories focuses on a small area of land where Ward was raised in Bernardsville, N.J., and emphasizes the importance of re-establishing roots by connecting personal lives with local history.

Ward also has worked as a history teacher in the classroom and as a group transformation facilitator in the experiential education field, where he has offered team-building and motivational programs for 12 years through his own company. For more information on his books and presentations, see www.gtwservices.com.

Wherever his future takes him, Ward is sure to carry with him the profound lessons he learned walking in the shadows of Lewis and Clark. He says that through his journey, he came to understand “how narrow our scope of life can be, how much energy is wasted on worry, and how, at the moment when we feel we are most alone, we are truly in the company of our most trusted and dependable guides. While Lewis and Clark have been credited with exploring the western wilderness, I believe the exploration of the greatest wilderness lies just beneath the skin in the hearts and minds of us all.”

FDU Magazine Home | Table of Contents | FDU Home | Alumni Home | Comments

©Copyright 2006 Fairleigh Dickinson University. All rights reserved.

For a print copy of FDU Magazine, featuring this and other stories, contact Rebecca Maxon, editor,

201-692-7024 or maxon@fdu.edu.