In reading The Day the Leader Was Killed, by Naguib Mahfouz, Fairleigh Dickinson University students in the Web-enhanced course Nobel Literature were puzzled at certain aspects of the story, which takes place in Egypt. One student wrote: “I did not completely understand why Elwan and Randa could not get married or, at least, what power was preventing them from doing so. I understand that he [Elwan] was unable to afford it, but do not fully understand the cultural/societal factors that prevented their marriage.”

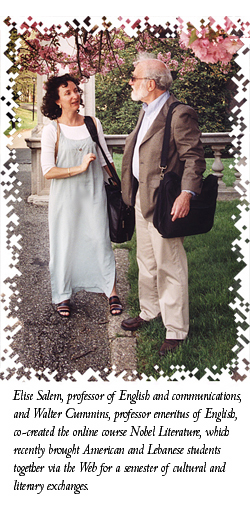

This question — one of several posed by New Jersey-based students to students taking the same course at the American University of Beirut (AUB) in Lebanon — was a hot topic of discussion in an exchange between students from the two countries. The course was taught in Lebanon by Elise Salem, an FDU professor of English and Communications on sabbatical, who with Walter Cummins, professor emeritus of English, directed the exchange between the students.

This response came from a Syrian student in Beirut, Mohamed Al Malazi, who says his society “resembles the Egyptian community to a large extent.”

I think many people in Syria consider it “ok” to marry people whom they do not love. This is, in my view, due to the economic status of Syrian people in general. The breadwinner, for example, finds it difficult to get by unless his daughters, if there are any, get married and lessen the living costs … In short, marrying men who may be “not unbearable” is seen by me as an act of helping a family by lowering its expenditure and thus supporting it financially.

Hillary Whitener, an American student, commented,

Wow, that was such a great response. … It is interesting to look at it from a different perspective, in the sense that it isn’t some horrible thing to marry someone for security. In every culture people do things that they do not enjoy or find rewarding in order to stay afloat financially. How different is it from devoting 50 years of your life to, let’s say, working in a coal mine in order to put food on the table?

Globalizing the Curriculum

Salem, who also serves as assistant dean for academic planning for the Maxwell Becton College of Arts and Sciences, reports that the English faculty at FDU’s College at Florham is working to “globalize” their entire curriculum. She and Cummins co-created the course, which examines texts including, in addition to Mahfouz’s novel, Jump, a collection of stories by Nadine Gordimer from South Africa; Chronicle of a Death Foretold by Colombian Gabriel Garcia Marquez; Jazz by American writer Toni Morrison; and selected works by Irish poet Seamus Heaney.

Salem taught the course in person at the American University of Beirut this past spring, and Cummins taught it to FDU students as a distance-learning course. “For our students,” says Cummins, “speaking directly with those of another culture on issues central to the course made the issues more pertinent, as well as providing background perspectives. Through technology we can provide ‘direct’ experience without the physical travel.”

Salem says, “It is invaluable for American students to have contact with Arabs/Muslims in this most difficult time in our history. It can break down misconceptions and false stereotypes built up by our media. Personal observation provides the best opportunity for growth and learning.”

Salem reports that Becton College’s department of English, communication and philosophy is now “adding literature from other cultures into most of its courses.” Salem also helped to further the study of Arab cultures by FDU students through the University Core required course Cross-cultural Perspectives. Becton College has recently established the opportunity to take a “culture” course in addition to its foreign-language requirement.

Salem is particularly well suited for her efforts to advance global education. A graduate of the American University of Beirut, she grew up in Lebanon. She holds dual citizenship, U.S. (her mother was American) and Lebanese, and is bilingual (English and Arabic). “This gives me an inherent advantage in teaching about other cultures,” she remarks.

The Power of the Pen

Literature has long been noted for its insights into humanity. As Salem says, “Literature is a great teacher of what it is to be a human being. It gets at the complexity of human existence — love, betrayal, conflict, war. These themes stand across cultures and across time. That is what makes literature such a great teacher of the human condition.”

And literature, especially Nobel Prize-winning literature, can be an ideal gateway through which to achieve cultural understanding. Several interchanges between the Middle Eastern and Western students related specifically to Middle Eastern cultures as a means to understanding more fully the situations set forth in Mahfouz’s novel. Feminist issues such as the right to an education, the ability to work and the wearing of the Muslim veil were discussed.

When asked how women feel about the restrictions placed on them in Middle Eastern countries, Rasha Nasser, an AUB student, spoke of rules of morality, “more than religious aspects:”

… our Islamic morality sees that a girl wearing a halter top with a mini skirt and high-shoes dangling off her feet is considered a kind of arousal to the male that sets his eyes on her. So to abolish this sin of Lust, Islam considers that a woman should wear something decent and suitable for her feminine posture. Then the veil came into the picture after it had been given down by God to Mohammad. Islamic woman could choose to wear the veil or not … One should really understand the religion before perceiving it as one that is strict and harsh and that doesn’t give any rights to women. [Islam] gives the women the respect and dignity that they should have.

The students were asked to discuss “how political history may be interpreted differently in the West and in the Middle East.” This led to exchanges about political and social issues such as President George Bush’s agenda for Iraq, about what their respective media had presented about the war in Iraq and other Middle East-based conflicts, and about the Middle Eastern/Muslim feelings toward Americans.

Beirut student Sawsan Maktabi describes the Middle East as a group of “countries where the geographical borders were marked by the old British Empire, where colonialism ruled for several decades, where the rich natural resources were and are still exploited by the West …”

Enriched with their newfound understanding of Middle Eastern cultures, online students in America were able to make insightful observations in their study of the novel. Jillian Villafane wrote:

After reading Mohamed’s response, I find myself struck by the vast differences between Muslim culture and our own American culture. Here in America we are taught to strive and persevere to achieve a status that is greater than the generation before us. Yet, we are not necessarily taught to share our newfound success and wealth with the extended and sometimes less fortunate members of our family. I think Arab cultures have a greater sense of loyalty and respect for family that is somewhat lacking in the United States. All of this makes me wonder which culture is truly the more fortunate.

Exploring New Worlds

This semester Salem is teaching Arab Women Writers: Feminism, Islam and the West, a “hybrid” course requiring attendance on campus as well as work online. In their investigation into the development of Arab and Islamic feminisms through the study of novels, poems, memoirs and critical essays as well as film, students were connected with Mohja Kahf, a global virtual faculty member born in Damascus, Syria, who is now a professor at the University of Arkansas. Her book, Western Representations of Muslim Women: From Termagant to Odalisque, is on library reserve. Kahf’s unique perspective as a Muslim woman raised and educated in the United States helps students to understand the experience of being both Muslim and feminist. In addition, two of Salem’s Nobel Literature students in Beirut have expressed interest in interacting with students in Arab Women Writers as well.

Raquel Montero, an American Nobel Literature online student, summed it up nicely in her post to AUB: “I agree that there is definitely a lack of understanding [between our cultures], but it’s opportunities like this, with technology and through education, that allow us to see someone else’s perspective and learn about their lives. Thanks for sharing.”

Elise Salem: Literally Piecing Together Lebanon

FDU Magazine Home | Table of Contents | FDU Home | Alumni Home | Comments