By Jane “Tinker” FoderaroEditor’s Note: |

Reunion in Turkey... A Marriage of Generations, CulturesCall it a form of global education. Or call it a personal odyssey. It was the summer of 2001, and there I was, after a 10-hour flight from New York, touching down at mid-morning in a strange new land to attend a wedding and participate in a whirlwind “learning experience,” all thanks to some of my former students. After sailing through customs, I entered the main greeting area of a large, modern international air terminal. Amid a sea of faces, I spotted my former FDU students — laughing, waving, jumping up and down, calling my name. I had arrived, joyously, in Istanbul, Turkey.

There was Selin Tunc, BA’97 (T-H), a native of Turkey who was soon to be married, along with Dimitra Tsvedos, BA’99 (T-H), born in the United States but whose family is from Greece, and Aspa Chatziefthimiou, a native of Greece, both of whom had just flown in from Athens to attend the wedding. They grabbed my bags and whisked me away in the front seat of a British SUV driven by Ismet Berkan, Selin’s fiancé and editor of one of Turkey’s major daily newspapers. As we raced toward the heart of the city, I glimpsed the exquisite mosques that dominate hills leading down to the sea. |

||

|

During the trip, Ismet simultaneously pointed out ancient landmarks, spoke to his newspaper staff on a cell intercom and answered my questions. In the back seat, Selin, a television scriptwriter, noted other places of interest (like the conservatory where she had studied piano for 12 years) and spoke on a phone with her producer. Dimitra, meanwhile, took a call on her own phone from New York, and Aspa’s camcorder already was rolling. How did a sixty-something lecturer at Fairleigh Dickinson University wind up in such an exotic place as Istanbul, Turkey, with so many young, dynamic, creative professionals?

It all started about seven years ago in a classroom in University Hall on the Teaneck-Hackensack Campus. Selin and Dimitra, who had met and become close friends at FDU, took my newswriting courses and wrote for The Equinox, the student newspaper, which I serve as adviser. I had met their friend, Aspa, a biology major, when she came to find them working late at night at the newspaper. One of my clearest memories of Selin in the classroom was her role in a debate that the rest of the class was “covering” for a news story. She argued, fervently, against the death penalty, citing all the reasons most European nations have come to reject it. But she had a formidable opponent, a native of Philadelphia, whose brother had been incarcerated, arguing just as passionately that “the homeless can’t get a shower, hot food or the medical attention that you get in jail.” (While in Turkey, I recalled that debate when I was reminded that no nation with the death penalty could be admitted to the European Union.) After they graduated, both Selin and Dimitra kept in touch with me. They would call when they were in New York, and the three of us once met for lunch at the Cedar Lane Grill in Teaneck. Dimitra later visited me at my home; and Selin sent wonderful letters about her creative adventures. In short, our relationship continued to grow. Two years ago, when global education was adopted as the University’s official mission, Selin and I discussed (via e-mail) different possibilities for mini courses involving the Turkish media. She was, after all, a logical contact. She had been a correspondent for a Turkish newspaper while she attended Fairleigh, she has worked on several documentary films since returning to Turkey, and she now writes television scripts for young professional audiences — all this while continuing to work on a master’s thesis in Ottoman studies. And now, of course, she was set to marry a top journalist who has been a foreign correspondent based in Washington, D.C. Selin often urged me to come to Turkey, and I said I would — one day. Then, last spring, she announced that she and Ismet planned to be married. Would I come? This time, I didn’t hesitate. Sights and SoundsThere was much to do on my arrival. First, we lunched at an outdoor seaside café where Turkey’s leading actress rushed up to Selin, reminding her that she, the actress, would do Selin’s make-up for the party following the wedding. (They had attended the conservatory together.)

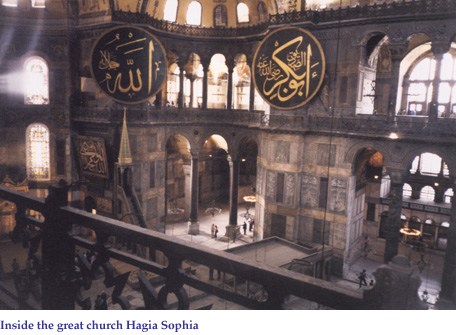

Next, we stopped at the couple’s home, an ancient three-story stone house, perched high above the city on a narrow, twisting and practically vertical street — with an interior that combined respect for the past with the sensibilities of young intellectuals (a Billie Holiday CD played in the background) plus two large dogs and spectacular views of the sea from iron balconies. We also toured the legendary Grand Bazaar, certainly the oldest, largest covered mall in history (20,000 people are employed in 4,000 shops), where we strolled along Byzantine corridors, examining Turkish crafts like brass trays, prayer rugs, porcelain bowls and beaded jewelry. This was followed by a respite in a tea garden where Turkish men converged after late-day prayer in a nearby mosque. After checking in at a charming, small hotel owned by a friend of Selin’s, we had dinner at a posh outdoor club on the Bosporus [the river separating Asia from Europe] with about 15 of the couple’s friends. It was hosted by Sezan, a woman who for years has been Turkey’s favorite singer and produced a single, “Kiss,” that last year ranked in MTV’s top 10. As a first-time tourist in Istanbul, I had but one priority. Ever since I took Art History 105 in college, it had been a dream to see Hagia Sophia (also spelled Ayasofya), the enormous domed Christian basilica built by the Greeks in 537, which has withstood the turbulence of history and still represents one of the greatest architectural feats of the world. What a privilege it was to enter that looming space with Dimitra and Aspa, who are both supremely proud of their Greek heritage. (Ancient hostilities remain between their country and Turkey, but Dimitra and Aspa repeatedly demonstrate how they’re part of the new global generation.)

They also took me to Yerebatan Sarnici, “the sunken cistern,” constructed by the Greeks in the fourth century to provide water should the city (then Constantinople) be under siege. Think of it — a huge, dim, underground waterway with meandering fish, punctuated by 336 marble columns supporting vaulted arches and domes. |

||

|

During my brief visit, I was struck by the many contrasts. There was the high-tech, high-energy pace of a teeming modern metropolis. (Taxis there make cabs in Manhattan seem as if they’re tied to a post!) But there also were sights and sounds of another way of life. From my hotel room I could see hundreds of sea gulls wheeling around the tall, slender, blue and gold spires of the magnificent Blue Mosque. I was awakened at 4 a.m. one day by the chanting of a call to prayer, broadcast via a public address system from the mosque. [Turkey is officially a secular nation, but the vast majority of Turks are Muslims.] While most of the younger women wear western clothing like jeans, mini skirts and high heels, many older women wear long coats and cover their heads with scarves — though I rarely saw women completely draped in veils. In spite of outward signs of a thriving commerce, there also were suggestions that the nation faced some difficult days ahead. I read in the Turkish Times, an excellent English-language daily newspaper, that interest rates were “down” to 224 percent! Some of Selin and Ismet’s friends feared for their jobs. A Wedding to Remember

The marriage remained the central focus of the trip. On June 15, Dimitra, Aspa and I went barreling in a taxi across a bridge to Asia. (Half of Istanbul is in Asia, the other half in Europe, and both look pretty much the same.) There, in a government building, Selin was married to Ismet during a brief civil ceremony — in maybe 45 seconds! Then we all drove back to “the other side” as the Turks say, regardless of which side they’re on, to toast the couple at an outdoor bar. But the real festivities were held the following day — and what festivities they were! More than 100 guests made their way up another ancient cobbled street where children played and old women in scarves leaned out of windows. At the top, we passed through a large wooden gate and entered a hidden, walled garden.

We were seated at long tables covered in white linen and fresh flowers. The bride was enchanting in a simple, long, white satin gown that she had purchased in New York. Wine began to flow, and platter after platter of traditional Turkish food was served — grilled lamb, fresh melon and cherries and plums, tomatoes and cucumber and cheese, roasted eggplant, fresh seafood, stuffed grape leaves, grilled chicken and much more. To my delight, I sat across from yet another of my former students, Alev Sungur-Badem, BA’98 (T-H), and her husband (they live “on the other side” in Asia), and they both wanted to know all the latest news at Fairleigh Dickinson. As darkness fell, Sezan and a half-dozen musicians — said to be the finest in Turkey — offered up both the latest hits as well as stirring traditional Turkish songs. Guests repeatedly jumped up to clap in time to familiar strains or dance to a mix of rhythms that suggested everything from gypsy to Arabic to French to rock. Was this a traditional Turkish wedding? Maybe not. But it surely reflected everything about the couple — their honesty, integrity, generosity, energy, dignity, humor and a love of their country and for each other. A magnificent cake was sliced and served near midnight; the young people then moved on to another venue to dance the night away; and I was driven far across the city to my hotel by friends of the newlyweds in a gleaming, purring Mercedes. I was still flush with the excitement of the evening, but the luxury of the car made me worry about the economic future of all the people who, during the last week, had been so hospitable and so open to me. Upon ReflectionThe next day, Selin and Ismet flew off to Rome and Florence for their wedding trip. I said goodbye to Dimitra and Aspa, knowing I would see them soon. (Dimitra visited me while on a trip to New York last August, and Aspa is back at Rutgers where she is pursuing an advanced degree in microbiology and genetics.) As I headed out to the international airport, my mind — rather unexpectedly — was filled with multiple issues involving global education. I recalled a class, perhaps five years ago, in which a Croatian student had conducted a “press conference” during the Serbian conflict, giving her family’s view of the horror. And I remembered how students had no idea exactly where the war was taking place. I probably wasn’t so sure myself.

As the taxi pulled up to my terminal, I kept saying to myself, “I need a world map in the classroom, a very big world map ...” On September 12, Selin called from Istanbul to make sure I was all right. I was deeply moved to hear the urgency in her young voice — even as I was coming to terms with the impact on my home state of New Jersey. Since then, Selin and I have shared our concerns about chances for maintaining peace in an unstable world. But I was relieved recently when she told me that the economic crisis in Turkey was beginning to ease. Then, on May 6, 2002, a student stepped forward to deliver her final speech in my Public Speaking class [part of the communications program]. Zeynep Kurtkaya of Istanbul grappled with her English to make an eloquent plea to her audience to “understand” her homeland. “We do not ride around on camels,” she said. “We are very western, Turkey is a member of NATO ...” I almost jumped to my feet to cheer her on. As she concluded, she received sustained and warm applause from her peers. In that instant, I realized that my trip to Turkey indeed had purpose — I had gained new insights for this one student in this one class and, I knew, for more to come. It also reaffirmed my conviction that students are our greatest resource, that we should listen to them very carefully, and help them to give voice to their experience — be it in our land or theirs.

About the AuthorJane “Tinker” Foderaro, senior lecturer of communication, teaches journalism courses and serves as adviser to the Teaneck-Hackensack student newspaper, The Equinox. A veteran newswoman, she spent most of her career at the Daily Register, Shrewsbury, N.J., where she was an award-winning reporter and then became city editor and later associate editor. She went on to become news director of four weekly newspapers owned by the Asbury Park Press, Neptune, N.J., and segued from the newsroom to the classroom in 1992, when she started teaching at Fairleigh Dickinson. Foderaro has served on the Press, Bar and Bench Committee of the New Jersey Press Association and the advisory board of the Journalism Resources Institute at Rutgers University, New Brunswick. |

||

|

FDU Magazine Directory | Table of Contents | FDU Home Page | Alumni Home Page | Comments |

|||