|

|

Rising from the Ashes

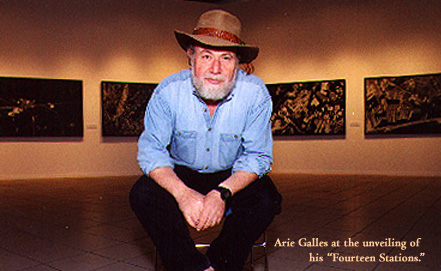

An Artist’s Memorial to Holocaust VictimsMuch has happened in Arie Galles’ life since he began the most challenging artistic project of his career. His mother passed away, his son became a director and writer in Hollywood, his daughter launched a professional career in England, and his best friend died. And through it all, the joys and the sorrows, Galles returned each day to his studio and stared some 30,000 feet down into the face of evil. For almost a decade, this art professor at Fairleigh Dickinson University’s College at Florham, Madison, worked on immensely detailed and powerful charcoal drawings depicting aerial views of 14 Nazi concentration camps. “I spent uncounted days peering into geographic Hades, mapping humanity’s darkest undertaking,” he says. The child of Polish/Jewish parents who fled the Nazis, Galles has titled his completed masterpiece, “Fourteen Stations/Hey Yud Dalet,” and offers this as his tribute to those who died in the concentration camps during World War II. He refers to the highly symbolic works as “icons for compassion and remembrance” of the human devastation caused during the Holocaust. |

|

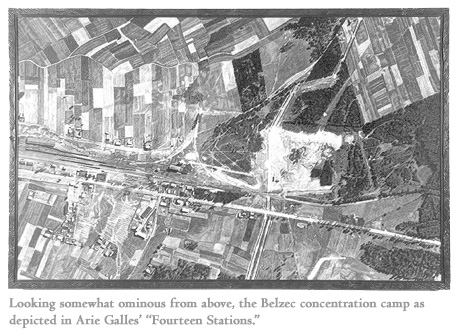

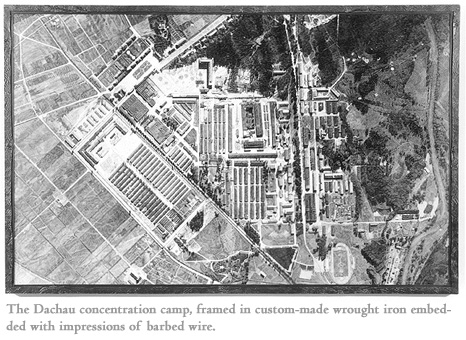

“Under no conditions can art express the Holocaust,” Galles says. “To withdraw art from confronting this horror, however, is to assign victory to its perpetrators. Therefore, each of us who has survived must affirm our humanity and existence. As an artist, and a child of survivors, I can do no less.” Galles used charcoal, in a way drawing with ashes, and each 44 ½" by 72" work contains a 14th of the Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead. “You will not see the writing, even if you know where to look, but by being aware of their presence one will have recited the Kaddish by the time all 14 drawings have been viewed. This is my Kaddish for those who perished. I say it most sincerely through my art.” The suite’s title corresponds to both the 14 Stations of the Cross and to each of the concentration camps built near railroad stations. “Hey Yud Dalet,” an acronym of the Hebrew phrase, “Hashem Yinkom Damam,” means “may God avenge their blood.” The drawings, with their layers of charcoal, are based on black-and-white photography and are accompanied by Jerome Rothenberg’s Gematria poems. The poems are derived from the Hebrew spellings of the camps, and are hand lettered by Galles over a ghost-echo image of each camp. The drawings and the poems are framed in custom-made wrought iron embedded with fossil-like impressions of barbed wire. What is perhaps most unusual is how the drawings depict a bird’s-eye view of seemingly ordinary landscapes. Galles studied hundreds of documents and reconnaissance photos to discover these images of concentration camps. His research led him to the National Archives in Maryland; captured German war documents in the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.; Royal Air Force archives in England; and to regional directors of several concentration camp museums in Poland. For Galles, the aerial views and physical distance from the camps were essential. “This was for me the only way I could draw this subject,” says Galles, whose aunt, uncle and cousins were murdered in the camps, and whose grandparents and other family members died during the war. “Many people have made art from the photos of the dead or from scenes of camp life, but that was not possible for me. I wasn’t there, and it was too horrible to imagine.” Still, his subject matter proved emotionally draining. “The most difficult part was dealing with the reality of the Holocaust and bringing it into my daily life. I felt that, for 10 years, I was strapped to the belly of a bomber, looking down.”

Galles persevered through the artistic and emotional challenges. “I found shelter and solace from the love of my wife, my children and my friends. And my other important coping mechanism was humor. I even tell funny jokes when I give lectures about this project. Hitler is not going to take my sense of humor away.” A Portrait of the ArtistFrom the time he was three years old, Galles knew he wanted to be an artist. “My father was a tailor, and his shop had these polished, deep-red painted floors. I used to climb up and peer through the windows at the many trains and tracks you could see from there. I would draw train after train after train on the floors with his soapy tailor chalks.” That Galles was even alive to draw was no small feat. After his parents fled from German-occupied Poland into Soviet-occupied Poland, and refused to accept Soviet citizenship, they were sent to a Siberian work camp. There, Galles’ sister died of diphtheria at the age of 5, and his brother, just three weeks old, died of starvation. Galles himself was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, in 1944 (his parents were released from the prison camp after the Nazis attacked Russia in 1941). Both Galles’ paternal grandparents died within a week of one another in the war camps in Siberia. Other relatives and family friends died in the Belzec death camp. His maternal grandmother, who stayed behind in Nowy Sacz, Poland, was hidden by a Catholic neighbor. She suffered from diabetes, however, and perished because she was unable to get the insulin that she needed. “What is amazing,” he says, “is that the man who hid her, and his friend, took her body to a Jewish cemetery at night and buried her there. These people risked their lives to do this final act of kindness.” After the war, Galles’ parents returned to Poland, and found their home in Sanok destroyed and the Jewish community annihilated. Growing up amid the devastation left a strong impression upon him. “I listened to accounts by neighbors of those dark times. Yet, the land on which such suffering took place was also the flowered field where my friends and I ran and played.” Not surprisingly, his art focused first on the Holocaust. His early works, as a teenager, included graphic images of Polish partisans being hung by occupying Nazi soldiers, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and German bombers in the sky. Galles explained that the Holocaust was a natural subject for him because it was a part of his life for as long as he could remember. “It was a part of everything in Poland. When you grow up among bombed-out buildings, three blocks away from a blown-up German tank, and you and your childhood friends play inside of it, how can you not become immersed in this subject?” Galles moved to America with his parents in 1958. His career soon took off, and his art moved from dark themes to a celebration of life. He became well known for his reflected light paintings, creations consisting of painted aluminum extrusions mounted vertically onto a white panel to depict an illusion from the reflected color light. His personal life likewise flourished. He met and married Sara and became a father to two children. In 1972, he started teaching at Fairleigh Dickinson University. “During this time, whenever I flew on an airplane I was mesmerized by the picturesque landscapes below.” This inspired Galles to begin an acclaimed series of works called “The Heartland Series,” colorful aerial views of American landscapes. Galles’ role at FDU expanded beyond teaching as he became chair of the department of visual and performing arts (1974–80, 1985–88) and gallery director (1988–1991). His relationship with his students, though, has remained his top priority. “I cannot teach them to be artists, but I can teach them to draw. I teach drawing in the same way that students are taught how to write sentences and make paragraphs. What sentences they are going to make, what stories they are going to write, that is up to them.” His students can often be found visiting the converted-barn studio behind Galles’ home in Madison. “I want students to see that I’m not a plumber or used car salesman faking it in trying to teach them art — they need to see that I do create, and that this is my life — I am an artist and a professor.” Galles the artist had by 1993 compiled an impressive list of accomplishments and accolades. His drawings and reflected light paintings had been exhibited nationally, including solo shows at the O.K. Harris Gallery in New York City and the Zolla Lieberman Gallery in Chicago. His works appear in private collections in the United States and abroad. He has been honored by arts groups and sponsors and was included in both Who’s Who in American Art and An Illustrated Survey of Leading Contemporary American Artists. Eventually, the subject of the Holocaust no longer figured in Galles’ art. As he explains, “I would get too upset. It was too close for comfort.” Then, in 1993, he visited the Wilf Holocaust Memorial in Whippany, N.J., and observed its octagonal room with walls divided into sections.

“It hit me instantly. I saw 14 black-and-white drawings of concentration camps as seen from the air. I remembered the 14 Stations of the Cross. I remembered Nobel Peace Prize recipient and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel’s words of witness to the ‘countless calvaries’ in the camps.” It was a calling that would consume him for nearly 10 years. The ‘Banality of Evil’Galles completed the arduous task with the help of two FDU grants and support from companies and individual donors. His decade of devotion included countless hours of painstaking labor. “I had to learn to be far more disciplined. I never realized how much work it was until it was complete.” The names for each drawing invoke the specter of inhumanity: Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, Bergen-Belsen, Dachau ... For Galles, drawing the camp of Belzec, where his relatives were murdered, was the most emotionally difficult. “I cried hysterically,” he says, as he recalls focusing on a spot on the ground that likely marked the final hundred yards members of his family, among hundreds of thousands of others, had been forced to run before being gassed. Galles says he’s not looking for a specific reaction from the audience. “A work of art is a two-way street. No matter how specific you make it, the audience will react differently because they all bring with them different life experiences.” He adds, though, that he senses most people will greet his “Fourteen Stations” with a “profound, introspective silence” and probably a feeling that these landscapes do not differ much from other common scenes. Echoing Hannah Arendt’s reference to the “banality of evil,” Galles adds that one of his main themes is the ordinariness of the scenes, the normal-looking rectangles and grid-like patterns of the terrain. But then it becomes apparent that those shapes and lines are gas chambers and trains carrying people to their death sentences.

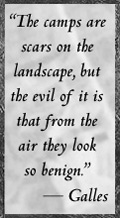

Galles says, “The camps are scars on the landscape, but the evil of it is that from the air they look so benign. You see how mundane those pictures look even as so much cruelty was happening. Evil doesn’t necessarily have to be ugly or come in horrible shapes. The Holocaust didn’t happen on a strange planet. It happened here.” The completed “Fourteen Stations” had its first showing at the Morris Museum in Morristown, N.J., this fall and was accompanied by various related events including a lecture by Elie Wiesel. When the work was displayed as a completed suite on the gallery’s walls, Galles says he felt the same stirring sensation he experienced as a boy coming to America and seeing the Statue of Liberty for the first time. “Fourteen Stations” will be shown at Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, from late January through March 2003 and then will be exhibited throughout the country and abroad. Galles hopes it eventually will find a home in a major city’s well-established museum. The praise for his achievement has already been great. A curator of one museum said, “Arie Galles’ skill and insight are necessary reminders to encourage us to re-examine our collective conscience.” The Return of ColorFor Galles, an emotional chapter in his life has concluded. The artist says that for years he didn’t place much stock in the idea that art is part of an individual’s healing process. “I did not paint when I was sad, angry or upset. I painted because of exuberance. I tried to light the world.”

After devoting so much of his heart and soul to “Fourteen Stations” and after dealing daily with feelings tied to his own family’s history, he says he has a newfound sense that art can help individuals cope with the most emotional subjects. “Art forces you to focus on what’s inside of you and how it’s reflected to, and in, the outside world.” Now his focus turns away from the dark images and from the nightmare of the Holocaust, and color returns to his studio. He has resumed his work with reflected light and depicting more heartening scenes — “colorful, joyous overviews of the American landscape.” After delving into the dark side of humanity, Galles goes into the future with an even greater appreciation of the importance of enjoying life: spending time with family and friends, going out dancing or enjoying an ice cream cone. “Life is good,” he says. “Life should be celebrated.” |

|

FDU Magazine Directory | Table of Contents | FDU Home Page | Alumni Home Page | Comments |

|